Bijay K. Danta

Mahapatra’s poetry obsessively returns to Odishan history, culture, ruins, and rivers that carry the bones of his ancestors, merged securely into the land. However, the poet—call it the poetic persona, if you will—recognizes that his right to this Odishan ancestry, granted to everyone born of this soil, is no longer unconditional.

1

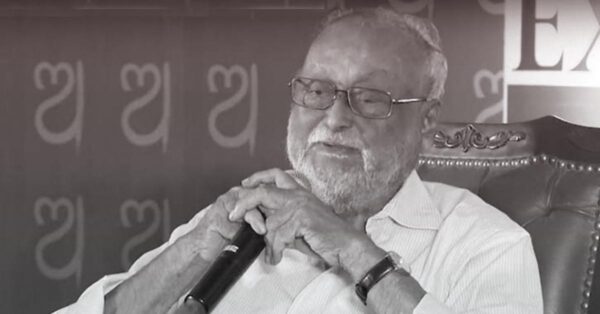

The death of Jayanta Mahapatra, on 27 August 2023, at the age of 95, was preceded dramatically by a letter, dated 20 June 2023, addressed to Dev Kamal Das, his nephew. In his letter, a last wish of sorts, Mahapatra asks his nephew to perform his final rites in a certain way. There are instructions on how his body should be ‘attired’ on his last journey, on where his body should be cremated, on who should conduct the funeral rites, and who should be consulted to ensure a smooth funeral. When Mahapatra wrote the letter, which was subsequently circulated in the media, he must have sensed that his ‘last’ letter—a paradoxically private and public act—would be read and analyzed endlessly by critics and admirers alike. This is a poet’s burden.

As he told his nephew that he wanted to be cremated in the Khannagar pyre—a Hindu cremation site in Cuttack—people were quick to harp on his ‘desire’ and frustrations over his final rites, saying his art completed an inner voyage. He was, according to these not-so-implicit interpretations, born a Christian—we know his grandfather converted to Christianity during the disastrous Odisha famine of 1866—but died a Hindu, at least by getting his body to be burnt, not buried. One can cite a mountain of self-serving quotes from Mahapatra’s poetry to substantiate such claims.

However, those looking for signs to confirm that Mahapatra had scripted for himself a sort of Hindu home-coming, were clearly rattled by his wish, expressed in the same letter, that Rev. Samuel Somalingam, the local pastor, be asked to observe a three-minute silent prayer near his body. There were of course people who dutifully cited Mahapatra’s public outbursts against the spiraling violence triggered by right-wing politics in India, and his decision to return his Padmashri award in 2015 with a well-publicized letter addressed to Pranab Mukherjee, the then President of India, as a confirmation of his unwavering belief in secularism. On the other hand, those who were skeptical of his poetry used his letter against the rise of intolerance to certify that the 1981 Sahitya Akademi Award for Relationship, a book of English poems, was an aberration.

Nobody wanted to know then, and few want to know now, if Mahapatra could live the life of a spiritual quester-poet who refused to name his god because his god was unnamable. As I said earlier, one may refer to the hundreds of prayer poems that Mahapatra is known for to argue that his poems are modern prayers. The prayers, one can say, are ironical, agnostic, and yet not atheistic. As a reader of his poems, I can only say that he was aware of a powerful tradition of Mahima saint-poets in Odisha—this is neither to confirm nor deny his faith in any specific religion—who wrote radical poems on their unnamable god. He drew on traditions that we are not always ready to understand. The fact that he wrote his major poems in English makes this job even more difficult.

Mahapatra’s poetry obsessively returns to Odishan history, culture, ruins, and rivers that carry the bones of his ancestors, merged securely into the land. However, the poet—call it the poetic persona, if you will—recognizes that his right to this Odishan ancestry, granted to everyone born of this soil, is no longer unconditional. While a part of him belongs to the land—hears the morning bells of the temples, watches the ceremonial procession of goddesses before immersion, inhales the red dust of the roads on the river bank, wanders all over his beloved town, greeting and being greeted by the community, feels the burden of the widows in front of the great temple, and almost rebels against the presiding deity as other poets had done before him—there is a part of him that recoils from the scene. He thinks his rights have been unjustly withdrawn, though never in as many words.

He repeatedly asks his muse, and torments himself by asking, if his grandfather’s conversion into Christianity must interrupt the participation of his soul—his poetry, not the social self that circulates in the social rites of the land—in the ancestral rites of the land. He wants to know if one’s ancestry can be circumscribed by a religion. There are no answers, though there are momentary resolutions. These resolutions come through interiorities of metaphysics, not religious following, externalized through poetic meditations in Odia bhajans and bhakti poetry. As a poet he draws on the traditional link in spite of the obvious challenges posed by religious boundaries.

The right to his Odishan ancestry—existential doubts over his rights—is a recurring theme in Mahapatra. His poetry refers to the temples of Puri, Bhubaneswar and Konark, built by the Eastern Gangas, whose ancestry can be traced back to the Gangas of Karnataka. One sees in several poems, written both in English and Odia, cryptic references to the work of these kings, who came to Odisha from elsewhere. The land and its people celebrate these ‘alien’ kings as they found a language—the language of devotion that the temples themselves stand for—to serve the land. Going deeper, he asks if there is any force—human or divine—that has the power to block the flow of one’s ancestral language into one’s veins.

2

Good poetry, it is said, explores more than it discovers. In this sense, for Jayanta Mahapatra, the quest is unending. Whether in his first poems, published in The Sewanee Review and Critical Quarterly, his cultural manifesto Chandrabhaga, his much celebrated A Rain of Rites (1976) and Relationship (1980), or the last letter he wrote to his nephew, there is this unrelenting search for an idiom that defies language. This is the language of poetry, neither Odia nor English, though he wrote in both languages with equal intensity.

The letter that I mentioned in the beginning of this essay carries a title, normally expected of a writer’s published work. It is written in a manner that allows the writer to ‘plot’ his funeral, forcing death to surrender to art. When I first read the letter, I was reminded of David Means’ Instructions for a Funeral (2020). In the eponymous story, a character leaves copious instructions on his last appearance before the community— “Please tilt the coffin slightly toward the room so that a view of my body is unavoidable”—in a way that allows him to direct the final scene of his life. In the story, the narrator ‘foretells’ big and small betrayals and dramatizes heartbreaks that only art can re-frame.

He finds a solution in art—this last wish is one such—that life denied him. Yet, to talk of a solution is misleading. To understand this one has to accept that Jayanta Mahapatra’s poetry is highly autobiographical, which is not to say that there is a case for digging out from his life—his family, his grandfather’s conversion during the disastrous Odisha famine of 1866, his emotional battles with his mother, his school life, teachers, love, marriage, his career as a physics teacher, his many false starts with poetry, rejections, fame, awards, insecurities, loneliness, relationships, his fractured spiritual life, his journey as a poet-singer-storyteller, his many encounters with infinity—those enchanting figures in his poetry. His readers have tried—and, not unexpectedly, failed—to unlock facts and figures behind the poems.

When we say that autobiography is a misunderstood genre, we perhaps refer to the mismatch between the demands that it makes, and the readers it gets. For, autobiography navigates between information and imagination. He tried his hand at memoirs, and wrote several versions of it, both in English and Odia. His memoirs—first published as Bhor Motira Kanaphule (2011), expanded as Pahini Rati (2013), and expanded once again as Bhor Motira Kanaphula (2022)—offer a unique and intimate window to his life. However, these autobiographical texts are more in the line of lyrical fiction than life writing texts. Bhor Motia Kanaphula (At Dawn, A Pair of Pearl Earrings) and Pahini Rati (The Night is Still There) allow the poet to return to a few incidents in his life, but only as points of departure. He refers to his dreamlike childhood and almost cuts out the sexual trauma he suffers while at school. He reproduces a few lines from his grandfather’s ‘history book’ on his conversion—a rare moment when history and poetry converge—that allow outsiders to look at a life-draining moment.

Jayanta Mahapatra’s poetry tries to re-cover this moment in the life of Chintamani Mahapatra, his grandfather, and ‘apostates’ like him. For whoever needed an explanation, the moment was triggered by the unspeakable pain of hunger and fear of death. For Chintamani Mahapatra and his descendants, however, this moment robs them of their access to their ancestry. Significantly, Mahapatra’s grandfather imagines the scene of his wife Rupavati’s conversion, and offers a dark epiphanic moment of revelation where the language used silences as much as it speaks. For a young boy, as Chintamani Mahapatra would have been then, conversion bore the mark of an inner trauma. This trauma was not felt or witnessed by anybody other than him. Chintamani Mahapatra only hints at what his wife, a seven-year old girl at that stage, must have gone through, captured in the haunting image of a wailing mother running after a bullock cart that carried her daughter away.

Years later, it was upto Jayanta Mahapatra’s father, a teacher at Ravenshaw Collegiate School, to explain to his wife and children what this moment was, and what this moment signified. Thousands perished in the 1866 famine. Some people were saved by the missionaries. The unforgiving orthodox community did not forgive the ones who survived by eating at shelters run by the missionaries. Conversion was first a way to survive hunger, and later, inevitably, to save oneself from the ultimate trauma of excommunication from one’s caste and community. Chintamani Mahapatra and his wife survived, but the price of conversion was terrible. In his memoirs, Mahapatra returns to this moment, but not to explain or justify the moment that would have legitimized what some people imagined was a return to his roots. Instead, he allows his poetic self to ‘speak’ his grandfather’s gnawing hunger, his grandmother’s desperate final gift to her mother running after the cart of the missionaries. She tore the string that perhaps tied her to her family and threw it to her mother. In this final act of ‘disaffiliation’ she gives away the little piece of gold attached to that string, and deliberately sacrificed her little possession and family link.

This kind of re-imagining is an act of poetic recovery, a brave act on the part of his grandmother. This is an attempt to re-insert oneself into one’s lost history. Faulkner does it for the American Old South. Wallace Stevens does it for the entire tribe of modernist poets. The idea is to speak to a community in a language that others do not understand. Mahapatra is a shamanic poet, if you will, who whispers into your soul in a language that you must train hard to figure out in its fullness. Access to his biography, either from the information that is already in the public domain or from what is given out in fragments of his poetry, might well give one a false sense of security while interpreting his poetry. A whole world of personal and immensely private symbols awaits you everywhere in his poetry. These make his poetry autobiographical. But the connections come from the poetry. You must look for epiphanies within the poems. His death allows us to re-imagine the poetry, and the poet. His last letter, his grandmother’s last gift, his own obsessive returns to history—these are windows to a poet’s soul.

Bijay K Danta is a professor of English at Tezpur University, Tezpur, Assam.