“For me, poetry is something that leaps out of an experience, like flames from a funeral pyre, at worst.“

Interviewed by Krishna Dulal Barua

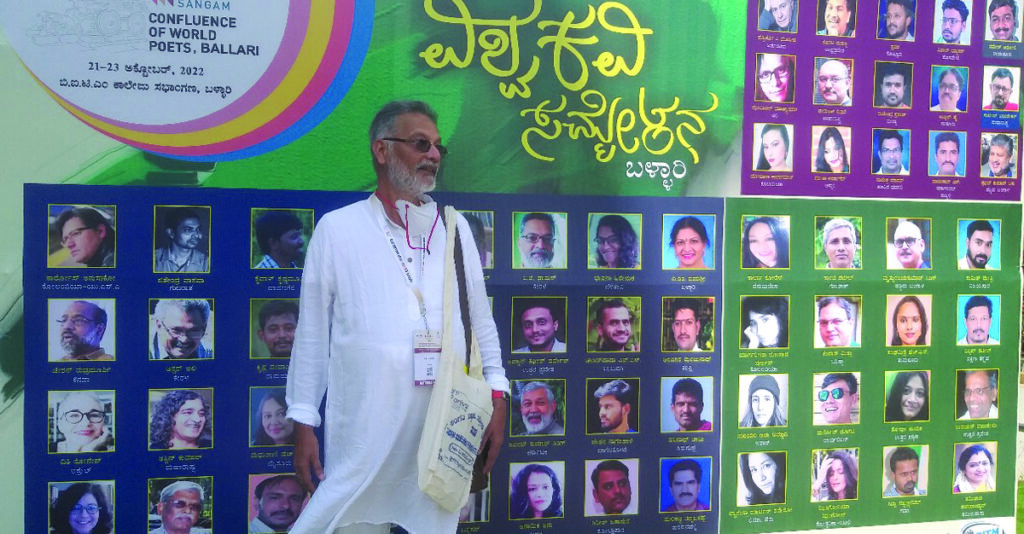

[Dr Alaichanickal Joseph Thomas, popularly known as A.J.Thomas, is a familiar name in the literary circles as a distinguished poet, translator, occasional short-fiction writer, critic and editor. Born on 10th June, 1952 in the district of Kottayam in Kerala, he had a literary bent of mind from an early age. As the years passed by, he had the great fortune of coming into contact with writers as acclaimed as Dominique Lapierre, Sir Angus Wilson, Salman Rushdie, M.T. Vasudevan Nair, Pritish Nandy, Kadammanitta Ramakishnan, D Vinayachandran, U R Anantha Murthy, Paul Zacharia and a lot of others, filmmakers G. Aravindan, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, P Padmarajan, Girish Karnad, and others, and actors like Sivaji Ganeshan, K P Ummer, Balan K Nair, Soman, Sukumaran, Akkineni Nageshwara Rao, Sridevi, Moon Moon Sen, Parvathy Jayaram, Mammootty and others, when he was working in the KTDC nature resort hotel Aranyanivas, Thekkady, in the Periyar Tiger Reserve. These writers and artists were tremendous sources of inspiration for him to pursue literature as a career. Thomas has been the tenured Assistant Editor, Editor and later Guest Editor of Indian Literature, the esteemed bi-monthly journal of the Sahitya Akademi for nearly twenty years. A.J. Thomas is a person always on the move remaining active as a resource person at seminars, conferences and literary festivals. He lived in Libya for six years from 2008 teaching English at Benghazi University. He is a permanent member on the panel of literary translators of the Sahitya Akademi. It is worthy of mention that his PhD thesis was on the linguistic and cultural problems of translation. He is a recipient of the Katha Award for Translation in1993 and the Hutch Crossword Award in 2007. His bagging of the AKMG Prize in 1997 enabled him to tour the USA, UK and Europe for four months. He held a Senior Fellowship of the Department of Culture, Government of India. He was an Honorary Fellow of the Department of Culture, Govt. of South Korea from 2011 to 2013. He has read his poems and made presentations in the Biennial Symposia of Asia-Pacific writers on invitation in Australia and Hong Kong, and also at conferences in Thailand and Nepal. Apart from his poems, stories and translations that have appeared in numerous reputed anthologies and journals, the notable publications of Dr Thomas include Germination (a collection of poems,1989), Bhaskara Pattelar and Other Stories (translation of Paul Zacharia’s stories), Keshavan’s Lamentations (translation of M. Mukundan’s novel), Ujjayini (translation of O.N.V. Kurup’s novel in verse), This Ancient Lyre (translation of O.N.V. Kurup’s poetry), Like a Psalm (translation of P. Sreedharan’s novel), The Deluge (translation of Omchery’s play) etc. He co-edited Sahitya Akademi’s two-book, four-volume 1700-pages Best of Indian Literature featuring the best short stories, poetry and critical essays published during the half-century from 1957 to 2007, in Indian Literature. His latest book, 50 Malayalam Stories which are modern classics, by 50 celebrated Malayalam short story writers, chosen from the early 1950s to the 2000s, translated and edited by him, titled, The Greatest Malayalam Stories Ever Told (2023), a best-seller over the last year, is in the short-list of the Crossword Award 2024 (Readers’ Choice), to be decided on 8th December 2024. Today, it is our proud privilege for Poetry without Fear to have this pre-eminent man of letters spare some of his valuable moments to share his feelings on a number of pertinent issues connected with literature and translation.]

Sir, please accept our regards. At the very outset, I, on behalf of PWF, congratulate you whole-heartedly for all your outstanding achievements in life till date. We remain hopeful for more in the years to come. Would you tell us in brief about your early upbringing and the major influences that drew you towards creative literature and translation?

I was born into an ordinary lower middle class Roman Catholic Syrian Christian family of Kerala, in Moonilavu, near Erattupetta, Pala, Kottayam District. I was lucky enough to have been able to live during the first ten years of my life, mostly alone with my mother, in a hill-side hamlet named Mechal five miles north-east of Moonilavu, my native village on the banks of the River Meenachil. My mother, though hardly literate, was a poet by nature who would talk to the animals and plants she tended to, as if they were human beings. Therefore, it was a daily poetic practice in action that I witnessed, and I too was drawn into that 24×7 engagement with practical poetry in my formative years. Mechal remains as an earthly paradise in my mind even now, along with my mother as my guardian angel, although I have not been able to return there for the last sixty years or so.

Thereafter, I moved to our family home in Moonnilavu, which was next door to our local Secondary School. This school had a small library, which had only seven English titles. One of them was Sohrab and Rustom, a tale which an Englishman had retold from Firdausi’s great Persian epic, Shahnameh. This book plunged me straight into English literature, in the very first year of my learning the language in school. The romantic, melancholy-nostalgic ethos of this narrative haunted my tender mind. The other books, in Malayalam translation, among which was The King of the Golden River, too helped to build in me the creative imagination. About this time, I remember writing an adventurous tale, an account of an actual trip we made to the local ‘Everest’, Mount Illickan, which was my first ever writing venture. This was also the time we had a textbook in Malayalam, Tenzing, about the Everest hero. I had also written a patriotic poem in metre, for our school magazine, and later, articles in our college magazine.

But I began writing poetry in English seriously during the two years I spent in Bandel, on the banks of the Hooghly, near Chinsurah, West Bengal, and a couple of months in Salesian College, Sonada, Darjeeling. This kind of poetry-writing continued sporadically during the couple of years I spent in Bangalore and Palmaner, near Chittur in Andhra Pradesh, for my studies. The three years I spent in Mananthavady, Wayanad, from 1973 to 1976, were the most formative. There, I worked as the private secretary to Bishop Jacob Thoomkuzhy; he had been freshly back from Fordham University, New York, after completing his Master’s degree in English literature. His entire literature library was at my disposal during those years.

Then, from 1976 to 1992, I lived in Thekkady, working in the KTDC’s nature resort hotel Aranyanivas, in the Periyar Tiger Reserve, during which time I met internationally and nationally famous writers and poets, artists and cultural figures who proved to be an enduring source of inspiration for my creative writing.

With which genre of literature do you feel more at home in expressing yourself?

Poetry, of course; and short-fiction writing. Literary translation, of poetry, fiction and drama, has been my most consistent engagement, in between.

With the evolutionary trends in social and psychological aspects, linguistic and literary expressions, too, are found to undergo changes with the passage of time. Do you subscribe to every form of such changes?

I do not really experience these changes consciously. I take to those changes as fish takes to water.

What are the trends in contemporary Malayalam poetry?

After centuries of versification, beginning with a bunch of modernist innovators like Madhavan Ayyappath, K Ayyappa Panikerand others around mid-20th century, generations of modernist, after-modernist, millennial and post-millennial poets have emerged in Malayalam. Even now, verse-poems appear regularly in periodicals; but there are also the latest formal experiments of poetry, like poetic-installations, taking place. The place of the bygone literary magazines has been taken over by poetry blogs, websites, e-journals etc. Experimentations are taking place on these platforms, and also on social media platforms.

Jorge Luis Borges once said in an interview that a poet has five or six poems to write. What would you say to that as a poet yourself?

I think what Borges said in effect is that you get five or six ‘default’ themes that reveal themselves to you, around which you create different versions of your experience vis a vis those universal themes.

How should a poet react to serious political issues?

I think a poet should react to serious political, social, environmental, or even personal issues, like everybody else does. But, on another level, a poet may or may not, adopt themes, metaphors, images from his/her experiences gleaned from such issues, in the writing of his/her poetry. If you mean whether a poet should resort to writing political poetry, it is his or her choice. But I would not personally like to write ‘propagandist’ poetry, or ‘sloganeering poetry.’ For me, poetry is something that leaps out of an experience, like flames from a funeral pyre, at worst. I would not presume that I can set the world right through my poetry. But, yes, I should communicate what I make sense of, through lived experience in this world.

I will share with you two poems I wrote very recently, moved by current events (published in an anthology last month). You will be able to see what I mean, reading those poems.

Death by Water

A glut of a downpour

A cloudburst or

A hillside opening up

Or a lake formed overnight in its womb

Breaks water

Delivering devastation.

We can’t blame it

On anyone

Least of all fate

It’s our own doing.

Life forms, breathing, wriggling, struggling

While in another phase, splashing, frolicking

All fun and games

Will be pushed out from your lungs

Within three minutes down under.

Why should I die in such a serene

Picture-post card lake, you’ll wonder.

But it’s the same case

For any one down under.

Therefore, if you are submerged

In your sleep, water level rising

In your cell, with no escape

You die like a rat in an immersed trap.

It can be actual

It can be factual

It can be virtual

It can be a process that fills

Your space up in millilitres

Like most of the slow-soaking

Policies, slipped in while you slumber.

Your element is certainly not water.

Death by Fire

Fire and brimstone at night, showered

On the slumbering Sodom and Gomorrah

Is what I remember first, of a vengeful act.

But there is a contrast.

The end result of that

Conflagration let loose

Upon the perceived sociopaths and sinners,

The residue of that great blaze,

Was an anticlimax.

It’s the waters of the Dead Sea

Where the living float

And even the half-living across the West Bank

Dare not test its waters

For no one knows what to expect

If you dive deep

Into the scriptures.

It’s all very similar,

Even same, in the beginnings

But what went wrong, where

Is in no one’s control.

Move further west

And you tread the burnt-out sands

And soil where milk and honey flowed

Once. And where

‘The walls came tumbling down.’

Jericho, the city of yore.

Further west

The apocalypse is afoot now….

All those bombs, missiles, falling on

Hapless sleeping women and children

While you sleep in your sleepy little hamlet

Unconcerned

Is death brought by fire

Through your acquiescence.

Death by fire,

Is everywhere.

During your tenure as the Assistant Editor, Editor and Guest Editor of Indian Literature, you had the enviable privilege of coming into contact with writers of all genres and ages across the country. What significant aspects have you noticed in modern Assamese literature? Have the writers from this region remained underrated?

I would never think so. Personally, I am the most impressed by Assamese and Odia writers, especially those earthy poets and fiction writers from the rural areas of these vast lands. If you mean why these literatures are not showcased enough, you might perhaps find the answer in the possible lack of adequately good quality translations, on a regular basis, especially in English and Hindi.

Once, during your visit to Assam, you had mentioned to me about a lot of similarities between our state and Kerala in the natural and social set-ups, the hospitality of the people and so on. Do you notice any similarities in the literary trends of the two regions?

I remember our discussion, Krishna, when I visited you at home in Nagaon, when I came over to visit Jiban Narah, I think in 2019. Yes, our two literatures have a lot in common— life in the watery expanses, in the rural outback, in the plantations, in the hills. A lot of poetry and fiction about the rural individual, lost in the fast-urbanising milieu, amidst the tenacious holding on to traditions and rituals. The height of tension between tradition and modernity is evident in its latest form in our art forms.

What was your primary concern as the editor of Indian Literature?

Actually, it was ensuring fair representation of all our national literatures in the journal. Then of course, assured representation of youth-writing and young-writing, while the seniors would anyway find their place!

You have travelled a lot both within the country and abroad. Do your travels influence the imagery in your poetry?

Naturally. But essentially, my ultimate experience will be something distilled from all those experiences, and not ‘direct reporting’ even through images and metaphors.

Your literary contribution through translations far exceeds your original writings. What could be the reason?

My sense of commitment to friendship. Almost 95% of the translations I have done are in response to personal requests from writer-friends. But I do have my ‘New and Collected Poems’, to come out; my stories, my novels, which I will soon sit down to. The ‘age of translations’ is almost over in my personal calendar.

How do you overcome the challenges in translations?

Through trying to be an honest and sincere communicator. Trying to be as faithful as possible to the original.

What can be done to improve translation skills? Are translation centres helpful in this regard?

Translation centres, translation workshops etc., are good for translation as group activity. For translation of poetry and drama, these are effective, especially if connected to some common cause like regional representation. However, I like to look at translation as an individual, creative activity. I am personally not a ‘professional’ translator. I do not like to be one. Especially in poetry and fiction translation.

The French poet, Jacques Prévert made a significant comment following his experiences in translation — a poem can be finished, a translation only abandoned. What exactly does he mean?

First of all, there seems to be a little confusion about this question. As far as I could trance from the Internet, Jacques Prévert is not the one who made this comment. It is Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the American Beat poet, trying to translate Prévert’s poetry, who made this comment. I shall quote from Alistair Campbell’s essay titled “Translating Jacques Prévert.”

‘A number of translators have sought to capture the spirit of Jacques Prévert. They include Teo Savory, Harriet Zinnes and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. “I translated these poems for fun,” Ferlinghetti tells us. But in the end there is dissatisfaction: “A poem can be finished, a translation only abandoned…”

This remark has come back to me again and again. For, the translation of poetry is not a self-contained linguistic act. It is an attempt to take a poem and to render it as one’s own while remaining faithful to the original. Even a linguistically straightforward, almost cinematographic poem like “Déjeuner du matin”, undergoes subtle changes from translator to translator. “Teaspoon”, “coffee spoon” or “small spoon” may all translate “petite cuiller”. What matters is the impact of the choice. How does the poem, as a whole, come across in English? One may translate such a poem with few liberties and feel that it still has something of the power of the original. By contrast, the assonance and ambiguity of “Chanson” – so simple, so beautiful in French! – defy replication.

Poetic translation is thus born of contradictory ends and for this reason must often ultimately fail. Yet, as Zinnes says, such failure is born of the love of the poetry itself. And that is its justification.

However, the famous French poet Paul Valery has said something just the opposite. “A poem’s never finished, only abandoned.”

Would you share one of your exciting experiences in translation?

It is about the ultimate advice that the Jnanpith awardee Malayalam poet, ONV Kurup, gave me about translating his poetry into English. “Thomas,” he told me: “Do not attempt to translate my mellifluous lines verbatim into English. Leave out all those fine-sounding words, which may have little relevance in English translation. Only hold on to what actually is poetry, and feel free to leave out the rest, if it does not work in English.” Many of our great poets or writers wouldn’t be as sagacious as ONV.

It has been quite an enlightening experience for us to learn more about you and have your views on different aspects of creative literature. Sir, thank you very much.

Thanks, Krishna and the editors, for this generous opportunity!

Krishna Dulal Barua is a prominent translator and writer based in Nagaon, Assam. He received the Katha Award for translation in 2005.