By Dr. Ananda Bormudoi

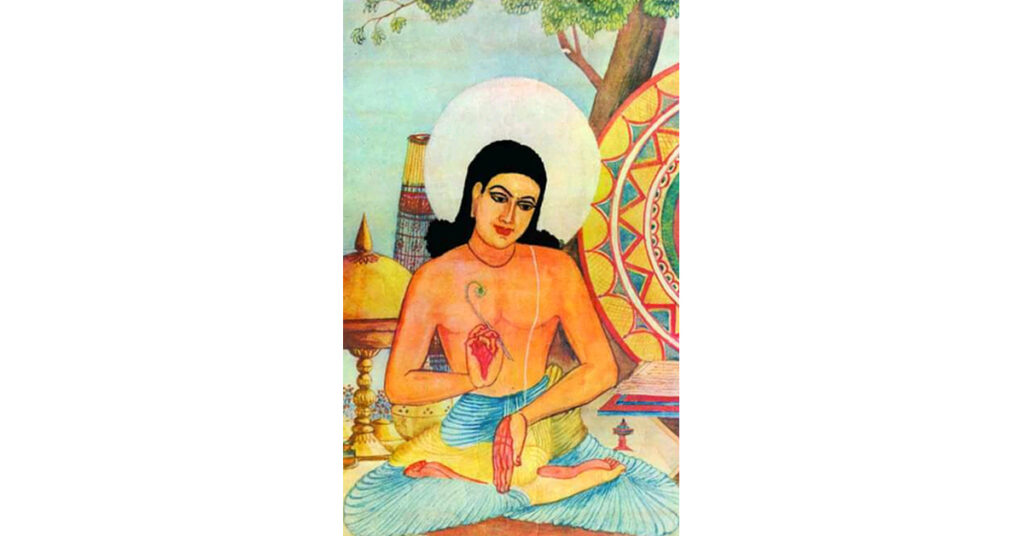

‘Apotheosis’ means the elevation to the status of a god. It implies that some individuals can cross the dividing line between gods and men. Sankardeva is an example of the apotheosis. He is believed to be an incarnation of God. It was not through any religious ritual that he was deified or raised to that status. Throughout the ages, the people of Assam most spontaneously elevated him to that status with love and gratitude. Anybody who takes stock of what Sankardeva did for the people must wonder how it was possible for one person to achieve in a lifetime all that he did. A profound scholar and a creative writer, Sankardeva could give the people all that they needed. He gave them poetry, music, dance, drama, sculpture, architecture, philosophy, religion, ethics, humanity and all that. He has always been an artist of the masses and a poet’s poet. He built the foundation of Assamese culture and he has directed the path of the Assamese writers and artist ever since.

Jyotiprasad said that anything new can be welcomed if it is assimilated to our culture and heritage and our tradition imbibed values mostly from Sankardeva. Some of the historians of Assamese literature have expressed an opinion that with the beginning of a new era of English education and culture, Assamese literature had a breach with the Vaishnavite era. But the breach, if there was any, was a purely temporary phase. The modernist poets also did not completely break away from the past. Religious teaching apart, our contemporary poets can also learn what poetry should be from the greatest ever Assamese poet. He could give classical poetry and music to the masses and this is a lesson that our poets can learn regarding communication with readers.

Also read: Poetic License

Those who have read Sankardeva’s description of autumn in Dashama must have noticed the distinctive features of Sankardeva as a poet. The spring is the most celebrated of seasons in poetry and in Assamese, poems on autumn are not many. One feels that no other Assamese poet so far has surpassed Sankadeva in description of autumn. Addressing the King, Suka says that summer has passed by and the features of autumn have set in. A description of autumn follows and the season becomes sensuous with all its colour and fragrance. Some of the features are like these—clouds have gone high up in the sky, water has become transparent, flocks of birds are clamouring in the lakes, lotus buds are ready to blossom forth and the night sky is studded with stars. But Sankardeva has not confined himself to a description of nature’s splendour alone. Happiness and sufferings of men and animals are getting bound up with the changes brought by the season. The central theme of the description is the relationship between nature and man, especially man’s material and spiritual life.

The changes which accompany a season are so vast that they defy any chronological description. We are usually not fully aware of all these changes. We suddenly feel and become aware of arrival of autumn when the dark clouds disappear in the sky. Sankardeva begins by referring to this feature. Summer rains cause great inconvenience to communication for animals and men alike by submerging roads and fields. The domestic animals suffer from want of dry land and they are pestered by mosquitoes and leeches. In Sankardeva’s picture of autumn, the pestering to the animals have been given a central place. The dark clouds of summer change into patches of white clouds here and there high up in the sky and the poet compares them to sages and the judicious. The sages become ascetic and temperate giving up their earthly desire and the dark clouds also give up their power to rain and turn into white patches.

Fish is a symbol of life in modern poetry and Sankardeva used it as a symbol of life in more than one sense. Shallow water fishes are generally not aware of the little depth of water in the ponds and drains that they are living in. They consider those water sources eternal. Human beings oblivious of death are compared to such fishes. As water dries up in the heat of the sun the shallow water fishes start swimming on the surface of water and shoals of such fish resemble the fate of people who neglect their duty to the soul.

Sankardeva organised the people of Assam with the help of religion spread through stories narrated in verse in a very highly interesting manner. He used different rhymes in his verse for that purpose. His verse is never monotonous. He knows the art of accelerating the speed of the narration by changing the rhyme scheme. In Kritan, the most popular of Sankardeva’s books, there are quite a few episodes of fighting and the poet describes them in a way that the readers and listeners can easily remember. It should be remembered that Sankardeva wrote for a society which was by and large illiterate. Most of those illiterate readers could memorise the episodes form the Kirtan simply by listening to them. In this content credit goes to Sankardeva for creating in his verse and adhesive quality, usually rare, for which they stick to the memory of the readers and listeners. He is also an absolutely first rate story teller in verse.

Depending on the effect that the poet wants to produce on his readers and listeners, Sankardeva sometimes brings his language of verse very close to the rhythms of the spoken language and at other times it distances itself from the conversational language. In ‘Prahalad Charit’ of Kirtan Hiranyakashipu’s austerity, concentration and devotion have been described in different terms. He was in deep contemplation of Brahma and finally Brahma arrived. Brahma was moved to pity by his devotee’s physical state of decay during his contemplation. The white ants built an anthill all around him and they had eaten up all his flesh and blood. And yet Hiranyakashipu was completely lost in his contemplation of Brahma. Being moved by devotion, love and concentration of the demon king, Brahma talks to him in a was as if a father talks to a son overwhelmed by emotion, “The flesh of your body has been eaten up by white ants/And yet you have been unwaveringly in contemplation.”

A great or eternal poetic line on a passage can be taken away from its context to make a meaning in other contexts of life. Sankardeva’s poetry abounds in such lines and passages. He was a writer with a thesis, an axe to grind. Many modern writers in their creative writings ignore the fact that their writings should offer delight to the readers through literature, the first requirement was to make writing interesting and delightful. People read only what is readable and the question of teaching comes only when a book is read and enjoyed. If a book is boring, dull and unreadable, the purpose of the writer to instruct fails. In this regard, Sankardeva is a poet of all poets. Rare ability to describe episodes in verse, change of rhyme scheme according to the turns and twists in an episode, religious instruction coming most spontaneously from an episode, most striking description of nature and environment, deep philosophical thoughts expressed in simple language, the ability to invent dramatic situations, splendid use of simile and metaphor and collocation of words have made Sankardeva a teacher of all poets and writers.

The Borgeets of sankardeva are profoundly philosophical but a popular Borgeet beginning with ‘athira dhana jana’ is popularly interpreted in a way as if the author was a nihilist to reject totally the meaning of all human relationships and material life. But the great philosopher simply stated that all human relationships, like everything on earth are in a state of a flux. They are changeable. W.B Yeats, the Nobel laureate, said in ‘Easter 1916’, “Minute by minute they change/… Minute by minute they live/ The stone’s in the midst of all.” In this context, Sankardeva resembles Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher, who said that all things are in constant flux regardless of how they appear to the senses. The persistence of unity despite change is illustrated by his famous analogy of the river: “Upon those who step into the same rivers, different and ever different waters flowing down.” In spite of the ever different waters flowing down every moment, the river is river.

What is the author searching for in the Borgeet? Is he searching for means to overcome death? To think of the constant flux and change is to be full of sorrows and the Borgeet is a prayer to Hrishikesh to open up a path of escape. In the universe of flux and change, Hrishikesh is the still centre and all motion and change originate from it. This Borgeet is a philosophical expectation on life and death. So long we are in the stream of time, we are mortal human beings. This borgeet can be read as the worries and anxieties of a man in the state of cyclical changes and flux. The changes are the causes of human sufferings. The image of the flux is sensuous and powerful: life is like a drop of water on a leaf of lotus and the mind is unsteady. The author of the Borgeet surrenders himself and prays to Hrishikesh: “Sripati, show me the path, tell me the meaning and give me advice.”

Jyotiprasad Agarwala wrote in an article on Assamese culture that Sankardeva was the giver of a full form to Assamese culture. Assamese culture blossomed forth as a result of the medieval Indian cultural movement’s impact on the talent of Sankardeva. While discussing the architecture of the Namghar, i.e. the community prayer hall, Jyotiprasad said, “the architecture of the Namghar is as simple as his Namdharma based on simple philosophy.” He was a genius who worked for the masses mostly poor and illiterate. The poor masses could not afford to spend money on religious rituals and he found an easy path for them. Chanting the name of Rama or Krishna would wash a person clean of all sins.

Jatindranath Dowarah in a poem on Sankardeva writes that nobody can write a proper biography of Sankardeva as his life spreads all over Assam. Bezbaroa has used this poem as the epigraph to his book on Sankardeva. The modern Assamese poets have realised that Sankardeva has given us religion, language, good manners, literature, culture, song, dance and drama and thereby his name becomes a synonym for Assam. Maheswar Neog, the poet-scholar, observes that different elements of Assamese culture most spontaneously merged with the religious movement of Sankadeva.