Ananda Bormudoi

Issue: Vol. IV, No. 2, August-October, 2025

Translating poetry is thought to be much more difficult than translating any other literary mode. Those engaged in translation studies have investigated into the causes. The studies have examined the different versions of translations of a single work and the statements of translators regarding the difficulties they faced in translation. The assessments are ultimately empirical. Susan Bassnett in her Translation Studies, mentions seven different strategies employed by translators of poetry. Phonemic translation attempts to reproduce the source language sound in the target language text. It also attempts an acceptable paraphrasing of the meaning. Translation of poetry may be literal in which the translator aims at word for word translation. Such translations may distort the sense of the original. Metrical translation aims at reproducing the source language metre and it does not consider the text as a whole. Some translators render poetry into prose to minimize loss. In rhymed translation, the translator has to keep the metre as well as the rhyme. It might end in a caricature of the source language text. Translating into blank verse may help the translator to achieve greater accuracy and a higher degree of literalness. The seventh strategy is interpretation in which the substance of the source language text is retained but the form is changed.

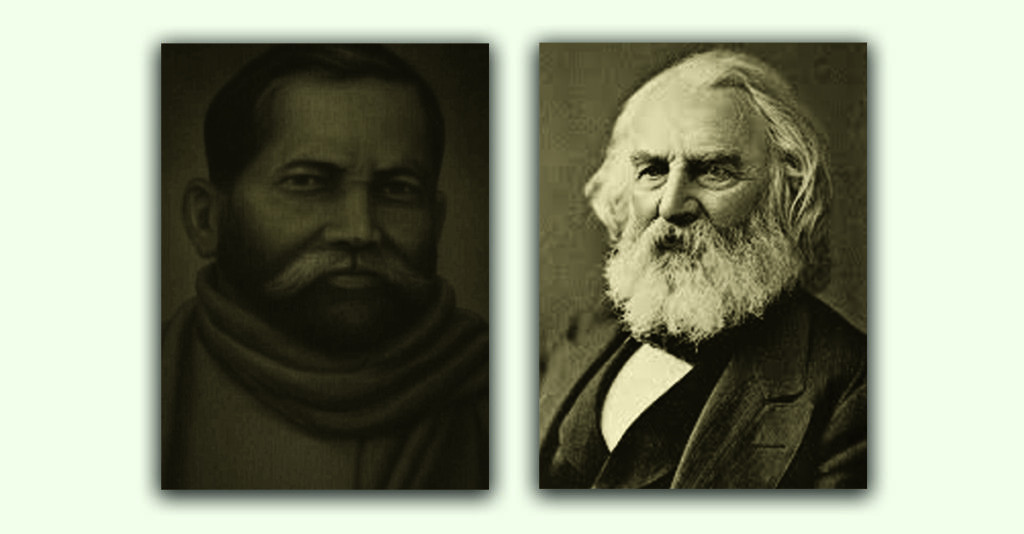

In the light of what has been mentioned above, now we can have a look at the translation strategy of Anandachandra Agarwala known for his excellence in translating English poems into Assamese. Let us take up Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Psalm of Life”. Longfellow’s poem contains a total of 212 words in nine stanzas. Agarwala’s “Jiwan Sangit”, i.e., the translated Assamese version, has fourteen stanzas and a total of 318 words. The Assamese poet has added to the translated version five more stanzas and one hundred and six more words. This physical fact of the translated version makes certain things clear. The Assamese translator has not rendered a word for word or literal translation. The word “psalm” in the title of the original poem refers to a psalm of life. The psalms of lament are a category of psalms in the Bible that express deep distress, sorrow and suffering, often directed towards God. The book of Lamentations also deals with themes of grief and suffering. The English poet disapproves of the idea put in the mournful numbers that life is an empty dream. The poem begins with an imperative, “Tell me not” and the imperative is to the psalmist. The speaker is asking the psalmist not to say that this life is unreal. Without referring to any psalmist, the Assamese translation of the first stanza conveys the idea contained in the English original. In Assamese, it reads like the speaker talking to the readers.

The second stanza of the Assamese translated version breaks away from the original. The second stanza in English begins with a broad general statement asserting the value of this life on earth, “Life is real! Life is earnest!/ And the grave is not its goal;/ “Dust thou art, to dust returnest,”/ “Has not spoken of the soul.” Translator decided to elaborate the idea in the first stanza which the young man disapproved and asked the psalmist not to lament. That was the unreality of life. The Assamese translator ignored the bold assertion in the original this life is real. It was not that the translator did not understand the intention of the English poet but it was his strategy and in translation the translator’s strategy is the most important thing. Why did Anandachandra Agarwala, in all probability, work out such a strategy break away from the original? What did he gain from that departure from the source language text?

The translator did not want to remain very loyal to the source language text. He felt a commitment to those for whom he translated. He was aware of the culture and tradition of the Assamese society. The spiritual tradition of the Assamese society may not absorb the idea that this earthly life is real and earnest. To make it acceptable to the target audience, the translator has twisted the sense of the original. Both Longfellow and Agarwala were keenly aware of the transience of earthly life but from that awareness they have developed different perspectives on life. As time is short and we have a lot of things to do, the English poem urges upon the readers to act in a way that “each tomorrow finds us further than today.” It is on the basis of work done that a person can attain immortality. That idea comes to the surface in the stanza, “Lives of great men all remind us/ We can make our lives sublime.” In the translated version, however, the emphasis is on the immortality of the soul. The fourth stanza makes it clear, “চকু কাণ নাক যাব হাড় ছাল সাং হ’ব/ মাটিৰ মানুহ তুমি মাটিত মিলিবা/ অবিনাশী নিত্যধন অমৰণ অভগন/ অনন্ত উন্নতিশীল আতমা জানিবা৷”

The Assamese translator is maintaining a rhyme in the translated version and makes the translated poem highly readable. No translation theory permits adding five more stanzas and one hundred and six more words to a poem of original nine stanzas and two hundred and twelve words. Anandachandra Agarwala’s end product is a memorable Assamese poem widely read by the Assamese readers. Many readers who have read it with pleasure and profit do not even know that the poem is a translation. Strictly speaking, the poem is not translation as such.